Mensalao

Brazil starts to hand out corruption sentences

Brazil's Supreme Court began handing out tough jail sentences in a landmark corruption trial that has tainted the legacy of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and spurred optimism that the South American nation is taking a step toward cleaning up government corruption.

Brazil's Supreme Court began handing out tough jail sentences in a landmark corruption trial that has tainted the legacy of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and spurred optimism that the South American nation is taking a step toward cleaning up government corruption.

The monthslong trial has centered on seven-year-old charges that senior government officials, bankers and consultants conspired to divert public money to buy votes in Congress and fund campaigns during the da Silva administration.

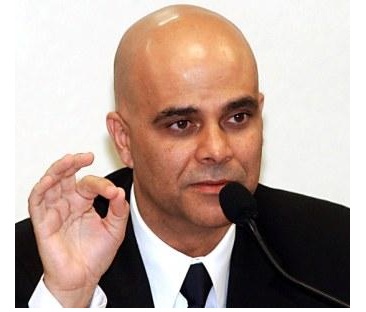

The court on Tuesday began handing down several multiyear jail terms to the first of 25 defendants convicted, Marcos Valério, the consultant convicted of being a key money conduit in the scheme. The court gave Mr. Valério, who it views as a central figure in the scheme, 11 years of jail time so far. The sentencing for Mr. Valério—who fought the charges and maintained his innocence—will continue on Wednesday.

The case, known here as the "mensalão" or the "big monthly allowance" for the payments congressmen allegedly received. The jail sentences issued Tuesday suggest the court is likely to also vote to jail other defendants such as José Dirceu, Mr. da Silva's former chief of staff and a onetime presidential hopeful convicted of being the scheme's ringleader. His sentencing could come as soon as Wednesday.

Mr. Dircéu denies wrongdoing. Mr. da Silva isn't charged with any crime and he maintains the vote-buying scheme didn't exist.

Soraia Mendes, professor of penal and constitutional law at the Catholic University of Brasilia, said the Valerio sentences were tough, signaling similar treatment for the other convicted participants. "Imagine, this is a positive surprise, that these things weren't swept under the table, that they didn't get away with it because of their high positions," she said.

The prospect of jail time for Brazilian politicians accused of corruption is new for a country where even voters have shown a high tolerance for graft. Former President Fernando Collor was impeached for embezzlement in 1992, but he was never charged with crimes and today serves in the Senate, where he ran the ethics committee for one term.

That culture of tolerance may be changing. The court's lead justice and its first black judge, Joaquim Barbosa, made the cover of the country's leading newsweekly under the headline: "The Poor Child Who Changed Brazil."

Experts on Brazil's legal system point out that the country still has a long way to go to root out corruption. The fact that the charges took seven years to come to trial are indicative of an inefficient legal system, according the legal experts. And Brazil's sentencing rules give privileges to politicians and college graduates, providing loopholes for upscale convicts to reduce jail time or avoid it altogether.

"This is still the exception that proves the rule, a baby step," said Matthew Taylor, an assistant professor at American University's School of International Service who has studied corruption in Brazil extensively.

In a sign of how groundbreaking the criminal corruption case was, it was heard in the Supreme Court—normally a forum for constitutional issues.

The convictions sully the legacy of Mr. da Silva, who remains one of the country's most popular politicians—a factory worker who climbed to the presidency and introduced policies to aid the poor. Officials in his left wing Workers Party, including Mr. Dirceu, have alleged that the Supreme Court is persecuting the party as part of right-wing conspiracy against it.

Defenders of the court point out that a majority of its justices were appointed by Workers Party presidents, including Mr. da Silva.

(Published by WSJ - October 3, 2012)